[Title page]

THE

HISTORY OF ENGLAND,

FOR

THE USE OF SCHOOLS

AND

YOUNG PERSONS.

BY EDWARD BALDWIN, ESQ.

AUTHOR OF FABLES, ANCIENT AND MODERN.

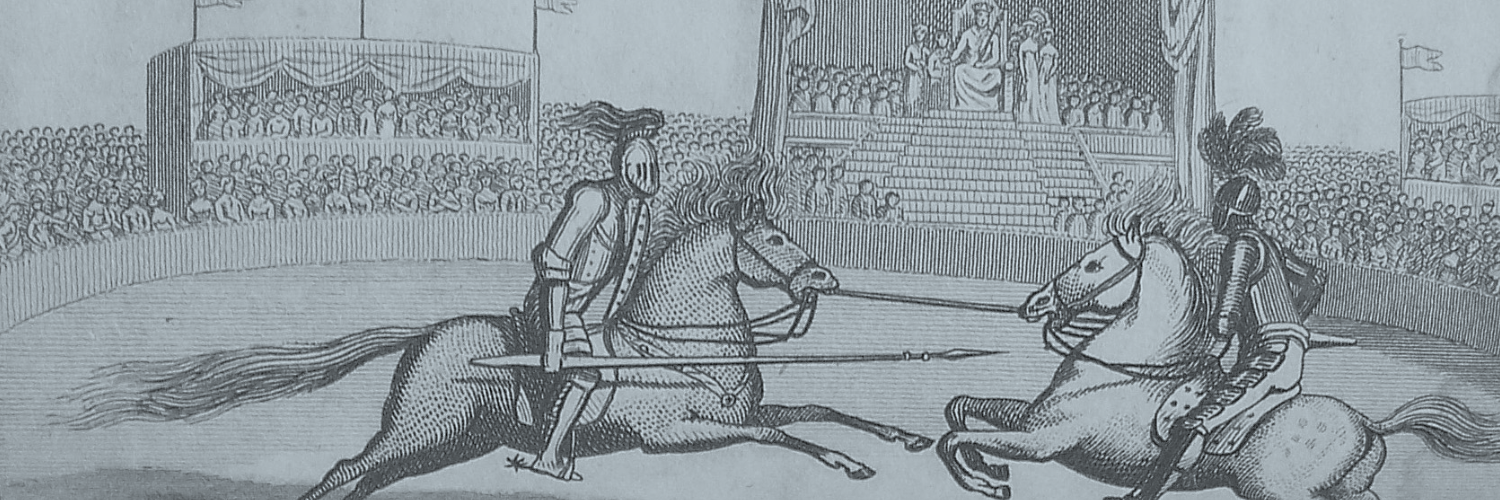

WITH THIRTY-TWO HEADS OF THE KINGS,

ENGRAVED ON COPPER-PLATE,

AND A STRIKING REPRESENTATION OF AN ANCIENT

TOURNAMENT.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR THOMAS HODGKINS, AT THE JUVENILE

LIBRARY, HANWAY STREET (OPPOSITE SOHO

SQUARE), OXFORD STREET, AND TO BE

HAD OF ALL BOOKSELLERS.

1806.

[Next Page]

PREFACE.

ENCOURAGED by the general acceptance which my Fables, Ancient and Modern, have found with the public, I have been excited to try how far a similar mode of familiar and playful writing might be successfully applied in the composition of History. Too long have books, designed for the instruction of children, been written in a dry and repulsive style, which the patience and perseverance of our maturer years would scarcely enable us to conquer. Too long have their tender memories been loaded with a variety of minute particulars, which, as they excite no passion in the mind, and present no picture, can be learned only to forget. I have lately seen Grammars of Geography, and Grammars of History, in which these faults, if they are faults, are carried to a height hitherto unequalled.

I have one criterion by which to form my judgment in these matters; and I will here plainly communicate it for the benefit of parents and instructors. I hold that those particulars of which an [end a2] accomplished gentleman and a scholar may without dishonour confess that he has no recollection, are a superfluity with which it is quite unnecessary to load the memory of a child. I have seen children, who can explain minutely the process of various manufactures, who can tell from what country we get our cochineal, and currently recite the particulars of the balance of trade between England and the four quarters of the globe. This certainly is not the very first branch of a liberal education.

It is not the boast of this little book that it contains a catalogue of five thousand remarkable events. My pages are not crouded with a variety of articles: they are so printed as to be agreeable and refreshing to the eye of a child.

I wished to give him a bird's eye view of the History of England, not to exhibit it by the aid of a microscope. For this reason I seldom or ever found it necessary to take down a book from my shelf as I wrote. I had nothing to do but with the great landmarks of history which can never be forgotten, and the strong impression which, once received, can never be obliterated.

That which constitutes the ultimate result of historical reading in the mind of a gentleman and a scholar, I was of opinion was precisely the first lesson of history I should wish to communicate to a child.

Yet, lightly as I ap- [end iv] pear in my narrative to skim over the surface of events, the reader will be surprised, when he comes to look at the Tables at the end of the volume, to see how great a mass of information this book contains. I am not without hope that the young reader will learn more from my pages, than from some productions on the same subject in two or three crowded volumes in twelves *.

Moliere, when he wrote his admirable comedies, was accustomed to read them in manuscript to an old woman, his housekeeper, and be always found that, where the old woman laughed or was out of humour, there the audiences laughed or were out of humour also. In the same manner I am accustomed to consult my children in this humble species of writing in which I have engaged. I put the two or three first sections of this work into their hands as a specimen. Their remark was, How easy this is! Why, we learn it by heart, almost as fast as we read it! Their suffrage gave me courage, and I carried on my work to the end.

*For a specimen of the manner in which this outline might advantageously be filled up for children, in those parts which are peculiarly instructive and interesting, the reader is referred to the Life of Lady Jane Grey by Theophilus Marcliffe. [end v]

Judging from the experiment of my own children, I am led to imagine that the sections of this volume might easily, as well as usefully, be committed to memory. The Tables at the end, are intended merely to fix the pupil's recollection of what he has previously learned. They may also convey to the inexperienced reader a vivid feeling, that there are other countries beside England, and other histories worthy to be read. In a word, they obviously serve as an introduction and remote prospect to the whole magazine of human sciences and arts. [end page vi]

HISTORY

OF

ENGLAND.

SHORT CHARACTERS OF THE KINGS OF ENGLAND.

WILLIAM I.

WILLIAM the Conqueror was harsh and severe.

WILLIAM II.

William Rufus was passionate and rash.

HENRY I.

Henry Beauclerc was an excellent scholar. [end B]

STEPHEN.

Stephen of Blois got the crown by a trick, but was hardly able to keep it.

HENRY II.

Henry Fitz-Empress was a man of spirit and sense, but was whipped at the tomb of Thomas à Becket.

RICHARD I.

Richard Coeur de Lion fought for the Holy Land with the sultan Saladin.

JOHN.

John Lackland was a pitiful fellow, and died of eating peaches: in his time was Magna Charta.

HENRY III.

Henry of Winchester was a poor creature, and had a troublesome reign of fifty-six years. [end 2]

EDWARD I.

Edward Longshanks was knowing and wise, but he loved war, and conducted it barbarously.

EDWARD II.

Edward of Caernarvon, a weak prince, was governed by upstarts, and cruelly murdered by his wife in Berkeley castle.

EDWARD III.

Edward the Third was the conqueror of France.

RICHARD II.

Richard of Bourdeaux was admirable while a boy, and contemptible when he grew to be a man; he was deprived of his crown and starved to death in Pomfret castle. [end 3]

HENRY IV.

Henry of Bolingbroke wrested the crown from Richard of Bourdeaux, and was miserable all the days of his reign.

HENRY V.

Henry of Monmouth won the battle of Agincourt on St. Crispin's day.

HENRY VI.

Henry of Windsor, half madman, and half fool, lost the crown that his grandfather had wickedly seized.

EDWARD IV.

Edward the Fourth was an arrant libertine, and took away the famous Jane Shore from her husband that she might live with him.

EDWARD V.

Edward the Fifth, and his brother, the duke of York, are said to have been [end 4] murdered in the Tower, while children, by their uncle, Richard Crookback.

RICHARD III.

Richard Crookback I believe was not crooked, and perhaps not a murderer of children; but he was conquered in battle by Henry of Richmond; and Henry was not contented to kill him, without making people think him a monster after he was dead.

HENRY VII.

Henry of Richmond was nicknamed by his courtiers the wisest of monarchs, but was in reality nothing better than a hard-hearted, scraping old miser.

HENRY VIII.

Henry the Eighth had six wives: he cut off the heads of two of them, [end 5] and put away two more: in his reign England changed from the Roman Catholic to the Protestant religion.

EDWARD VI.

Edward the Sixth was nine years old when he began to reign, and sixteen when he died: he was a good boy, studied Greek, and was a towardly scholar.

MARY.

Bloody queen Mary burned three hundred Protestants in four years, because they did not think just as she did, and would not tell lies about the matters.

ELIZABETH.

Queen Elizabeth of all her sex had a genius best fitted to govern; but she was apt to swear, and box her [end 6] ministers' ears; in her time was the Spanish Armada.

JAMES I.

James the First would have made a very good schoolmaster, and a very good schoolmaster is a most excellent member of society: what a pity people should be put to a business they are not fit for!

CHARLES I.

Charles the First loved and understood the works of Shakespear and Raphael and Titian; he was a noble and accomplished gentleman; but he was not a good king, and he had a hard fate; his subjects went to war with him, defeated him, and cut off his head.

CHARLES II.

Charles the Second had a good deal of wit, but made a bad use of it; he [end 7] never said a foolish thing nor ever did a wise one.

JAMES II.

James the Second, like his grandfather James the First, was put to a wrong trade; he was more like a monk, than a king; he wanted to make us Roman Catholics, but we were a hundred and fifty years too old for it.

WILLIAM III.

William the Third was a Dutchman: we sent for him over, because we would not be made Roman Catholics by James the Second; and so James was sent away, and William reigned in his stead.

ANNE.

Queen Anne was a quiet, good-natured woman, and wanted nothing but [end 8] peace: but the duke of Marlborough was her general, and won several famous battles for her abroad; his duchess governed queen Anne at home, and would sometimes affront her majesty, and the make the queen beg her pardon.

GEORGE I.

George the First was invited from Hanover to preserve the Protestant religion: queen Anne wanted to have given the crown to her brother, the son of James the Second; but he, like his father, was a Catholic: in 1715 there was a rebellion in Scotland in favour of queen Anne's brother.

GEORGE II.

George the Second had to contend with the rebellion in 1745; the rebels were defeated at Culloden by [end 9] William duke of Cumberland, the king's son.

GEORGE III.

In the reign of George the Third, who has reigned between forty and fifty years, happened the Independence of America, and the French Revolution: Lords Rodney, Howe, Duncan, St. Vincent and Nelson have adorned this reign by their victories at sea. [end 10]

HISTORY

OF

ENGLAND.

THE BRITONS.

THE history of the world is divided into Ancient and Modern History: the birth of Christ, who was the great author of the Christian religion, is the event at which Ancient History ends, and Modern History begins.

The inhabitants of Britain before Christ wrote no books; therefore all that we know about them is obscure and imperfect. [end 11]

The best writers of books in the period before Christ were the Greeks and Romans: the Greeks wrote something about the Ancient Britons; but the first accurate account was written by Julius Caesar emperor of Rome, about fifty years before Christ.

The first inhabitants of Britain, that we know any thing about, came over from France, anciently called Gaul: they had among them a set of learned men called Druids.

These learned men perhaps could neither read nor write; but they studied the stars, and the system of the heavens, commonly called astronomy; and they composed so many verses upon astronomy, and history, and morality, and religion, and other subjects, that Julius Caesar says it took their pupils twenty years to learn them all by heart: the Druids were lovers [end 12] of Gods and good things, and taught valuable precepts to their scholars.

As the time when the Druids flourished in Britain was before Christ, they could not be Christians; they were very devout, said many prayers, sung many hymns, and made many sacrifices: I am sorry to say, that they sometimes sacrificed (that is, killed) men at their altars, and thought to please their Gods by it: the principal objects of their worship were the sun, moon and stars.

THE ROMANS.

ROME, the famous mistress of the world, was at first a poor village, made up of clay-built huts; but in time grew rich, and conquered first all Italy, and then almost the whole known world: [end 13] the last country that the Romans conquered, was Britain.

Julius Caesar, first emperor, invaded Britain, but did not conquer it: a Roman province and government were not established here, till under the fourth [crossed out and fifth written by hand] emperor Claudius: the Britons struggled a long time against their conquerors; the greatest of the ancient British heroes was Caractacus.

The Romans made quite another thing of Britain from what they found it: the Britons lived in mean huts, and when many of these stood together, they dug a deep ditch round the whole, and called it a town: there remains however of the Ancient Britons the ruin of several stupendous structures built for religious purposes: the chief of these is Stone-henge on Salisbury Plain.

The Romans built beautiful towns in many parts of England in the best [end 14] style of architecture, and adorned them with theatres, palaces and temples; so that Britain became in length of time almost as fine as Italy itself: Greek was studied here, and Latin became the ordinary language: the Romans were fond of teaching us, and found us very apt scholars: Constantine the Great and others, were advanced from the government of Britain to the throne of the empire.

The religion of the ancient Romans was the religion of Homer and Virgil: their Gods were Jupiter and Juno and Mercury and Mars and Minerva and Venus: there were a great many of them: an ancient writer counts up thirty thousand

: the Romans hated the Druids, because the Druids taught their followers the love of liberty, and the Romans, before they landed here, were become slaves: so the Romans murdered the Druids wherever they [end 15] found them, and destroyed their religion and learning.

Constantine the Great, established the Christian religion in Rome, about the year of our Lord 324: the provinces followed the example of the capital, and Britain, like the rest of the empire, was soon furnished with bishops and clergy, who expounded to the people the doctrines of Christ and his apostles: the Roman government in Britain lasted till the year 420.

THE SAXONS.

THE Romans were once the most frugal, temperate and high-spirited people in the world: in length of time they became wasteful and luxurious, and betook themselves to the most disgraceful excesses: under their republican government they were free, [end 16] under the emperors they were slaves: in the former period they conquered the world, in the latter they were conquered themselves.

When the Roman empire became incapable of defending itself, it was overrun by the Goths, and Vandals, and Huns, and Lombards, and Ostrogoths, and twenty barbarous nations, who poured down upon the civilized world from the frozen regions of the north.

Britain was seized by the Saxons, who came from the shores of the Baltic to this island in their ships: the particular race of Saxons who came here were Anglo-Saxons; and from them the country they seized was for the first time called the land of the Angles, or for shortness England.

The Britons in general made but a poor resistance to their conquerors: this was not the case however with all; [end 17] the bravest among them retired to the mountains of Wales and Cornwall, and were never entirely subdued by their invaders.

Among the Britons who boldly resisted the barbarous and ignorant Saxons, there was one very famous man, who was called king Arthur: he fought any battles, and always showed himself a brave soldier, a good patriot, and a man or honour: he was killed in battle about the year 546: a great many stories have been told of him, some true, and some false, particularly of the adventures of his knights of the Round Table, though knighthood was not invented till some hundred years after his death: Spenser, one of the best of the best of the English poets, wrote a very long about him and the Fairy Queen.

[end 18]

THE HEPTARCHY.

THE founders of the Saxon government in England were Hengist and Horsa, two brothers; they conquered Kent; their countrymen on the shores of the Baltic, heard of their success, and followed their example; one part of England was seized by them after another; and the Saxons erected seven kingdoms in England, which are called the Heptarchy.

The barbarous Saxons abolished the Christian religion among us: they were quite as successful in teaching us ignorance, as the Romans had been in teaching us knowledge: the very ideas of the Christian God and his son were lost: and historians have supposed that, soon after the death of king Arthur, not a book was to be found in the island.

The Saxons however had a religion of their own, and Woden or Odin was [end 19] their principal God; the names of several of their Gods are preserved to us in the names of the days of the week, Sunday and Monday are the days of the Sun and Moon, Tuesday is Tuisco's day, Wednesday the day of Woden, Thursday of Thor, Friday of Friga and Saturday of Sater: it is usual to consider the Saxons as more peculiarly our ancestors than either the Britons of Romans; because they were Angles, we are called English; and, though the language they spoke (which was the Saxon) has changed its name among us, it differs not otherwise from that we speak now, than as almost all languages alter in the course of some hundred years.

In the year 596 the pope of Rome sent over some monks to convert the Saxons to the Roman Catholic faith: they went from one kingdom of Heptarchy to another, and in a short time all the Saxons became Christians; [end 20] the better sort learned to read and write; England produced students and authors, and gradually became adorned with churches, monasteries and cathedrals.

Monasteries are large houses full of monks or nuns, people who have taken a vow never to marry, and to spend all their lives in saying their prayers, and reading good books.

THE MONARCHY.

IN the year 800 Egbert, king of the West of England, put an end to the Heptarchy, and made himself first king of England.

His grandson, Alfred, was the noblest king that ever sat on this, or perhaps any other throne: he collected all the good laws that had ever been made by any of his Saxon ancestors, and caused them to be observed: the [end 21] Saxons, though a barbarous people, were endowed with good sense, and cultivated the love of liberty in the dark and unpleasant climate they came from: many of their laws are excellent, and are the laws and principles of the English government to this day.

They were times of great barbarism that Alfred lived in: he did not learn to read till he was nine years old, and then only because he begged to be taught: there were no clocks in the island, and Alfred invented a way of measuring time by candles which were made to burn eight hours apiece: he allowed himself eight hours in every day for sleep and his meals: eight hours for study, and eight hours for the public duties of his government; which he discharged with an exactness, an impartiality, and a wisdom, that almost exceeded human capacity. [end 22]

THE DANES.

BUT Alfred was not allowed to spend his life in exertions to promote the private happiness of his countrymen: the Danes, who inhabited almost exactly the same region from which the Saxons had come, sailed over to Britain in their ships, with an inclination to treat the Saxons now, as the Saxons had treated the Britons before: at one time they were so successful, that Alfred lost his army, and was obliged to hide himself for weeks in the disguise of a servant in a poor man's cottager: it was here that the cottager's wife gave him a scolding, for letting her cakes be burned while he sat by the fire where they were toasting.

From this retreat he contrived to send messages to his friends, and got together a new army: he then dressed himself like a harper (a singer of fine [end 23] old ballads like Chevy Chase, to the music of his harp,

) and went into the Danish camp: there he played and sung before the king: and, having found that the Danes, now they saw no enemy, minded nothing but dancing and drinking and amusements, he went away, and came back with his soldiers, defeated the Danes, and obliged them to go home to the shores of the Baltic.

The Danes were a braver race of men than the Saxons: when the Saxons came over to Britain, and settled among the remnants of Roman luxury, they grew effeminate; when they became Christians, it was but a poor religion that the tyrannical popes and ignorant monks taught them, and they lost the fine old songs and ballads, which celebrated the courage and virtues of their ancestors, that they had learned at home: the monks told them they must sing nothing but Psalms. [end 24]

The Danes, who staid at home in their northern climate, amidst stupendous rocks and wild scenery, continued to sing the songs of their ancestors, and made better: their poets are called Scalds, and their compositions the Runic or Scandinavian poetry: some fine specimens of it have been put into English by Gray, author of the Elegy in a Country Church Yard:

their religion was the same as that of the Saxons had been.

The Runic poets are the inventors of those charming tales about giants and fairies, and dragons and enchantments, which in this island have always afford an agreeable exercise for the fancy of children.

The Danes felt a singular animosity to the Christian religion, especially to the monasteries in which so many persons of both sexes lived in idleness and [end 25] effeminacy: one measure which marked the progress of the Danes wherever they came, was the burning of monasteries.

The Saxons perhaps never produced a truly great man, beside Alfred: he stopped for a while the inroads of the Danes: but some time after his death they became more frequent and formidable: the pusillanimous Saxons gave them money to go away, and the Danes, when they had spent what they carried off, came back to get more: Alfred died in the year 900; and about a hundred years afterward Canute, king of Denmark, made a complete conquest of England, and after a reign of eighteen years in this country, left the crown to his sons: the Danes had by this time embraced the Christian faith.

The sons of Canute died without children; in consequence of which the Saxon royal family resumed the throne [end 26] in the person of Edward the Confessor: in his reign lived Macbeth, king of Scotland, upon whose story Shakespear has founded the finest of his plays.

THE NORMANS.

AFTER Edward the Confessor, came in the Normans: the Normans were in the finest race of men that ever the frozen north poured forth from her recesses: amidst the meanness and ignorance of the middle ages, they appear like a superior race of beings

: they conquered, and settled themselves in possession of, a part of France and Italy, together with the islands of Sicily and England.

They were the great promoters of knighthood and chivalry: they taught us generosity in our conduct to men, and deference and politeness to the [end 27] ladies: even toward their enemies in war they were generous, warm-hearted and humane

: the Greeks and Romans were barbarous in their manners compared with them: the Greeks and Romans were austere and despotical in their conduct toward the tender sex, and the Romance first made a show to the populace of the unhappy kings they had conquered, and then threw them into dungeons to starve: many of the best qualities of the present English character we owe to the Normans.

Edward the Confessor, during the reign of the Danes, had lived a banished man in Normandy; and he so greatly admired what he saw, that, as he had no children, he appointed William duke of Normandy, afterward called William the Conqueror, his successor when he died, in the throne of England. [end 28]

A TABLE OF THE KINGS AND QUEENS

OF ENGLAND, FROM THE CONQUEST

THE NORMAN LINE.

A.D.

William I. began to reign 1066

William II. - - - - 1087

Henry I. - - - - - 1100

Stephen - - - - - 1135

THE PLANTAGENETS.

Henry II. - - - - 1154

Richard I. - - - - 1189

John - - - - - 1199

Henry III. - - - - 1216

Edward I. - - - - 1272

---------- II. - - - - 1307

---------- III. - - - - 1327

Richard II. - - - - 1377

THE HOUSE OF LANCASTER.

Henry IV. - - - - 1399

-------- V. - - - - 1413

-------- VI. - - - - 1422

[end 29]

THE HOUSE OF YORK.

A.D.

Edward IV. began to reign 1461

----------- V. - - - - 1483

Richard III. - - - - 1483

THE HOUSE OF TUDOR.

Henry VII. - - - - 1485

------- VIII. - - - - 1509

Edward VI. - - - - 1547

Mary - - - - - 1553

Elizabeth - - - - 1558

THE HOUSE OF STUART.

James I. - - - - - 1603

Charles I. - - - - 1625

Charles II. - - - - 1649

James II. - - - - 1685

THE REVOLUTION, 1688.

William III. - - - - 1689

Anne - - - - - 1702

George I. - - - - 1714

George II. - - - - 1727

George III. - - - - 1760

[end 30]

THE

NORMAN LINE.

WILLIAM I.

1066

WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR WAS HARSH AND

SEVERE.

WILLIAM the Conqueror was a prince of great abilities, and formed an entirely new plan of government for this country, agreeably to what is called the feudal system: he divided the soil into knights' fees, baronies and earldoms, and gave them to his Norman followers: a knight, a baron and an earl, meant then the lord or proprietor of a certain province or portion of land, by the name of which the knight, [end 31] the baron, or the earl, was commonly known.

William the Conqueror despised and ill-treated the Saxons, because they were not so wise and so brave as his own countrymen

: French was the only language spoken at court; and one circumstance has taken place in consequence, in English, that belongs to no other language in the world; which is, that we call animals kept for food by one name while they are alive, and by another after they are dead: the Saxons fed the animals, and the Normans ate them:

the names therefore by which they are called while alive are Saxon, and when dead are French: the Saxon, bull, ox, cow, calf, sheep; the French, beef, veal and mutton.

William the Conqueror, when he became king of England, continued duke of Normandy, that is, lord (in subordination to the king of France) [end 32] of a valuable division of that country: his successors acquired other provinces in France, till they became feudal, or inferior, lords of a third part of that kingdom.

A feudal lordship was at first a very humble and dependent station: the person who held it was bound to perform certain menial offices for his superior, such as taking care of his dogs, superintending his wardrobe, or airing his shirt (hence come our master of the horse, groom of the stole, and lord of the bed-chamber); he swore the obedience, on his bended knees, and with his joined hands put between the hands of his lord-paramount; when he died, his successor paid a fine to be permitted to have the land, and if he were under age, was placed at the direction of his superiors; but the feudal lords grew more and more powerful, till they became little less than kings, each over his inheri- [end 33] tance, and seldom paid much attention to those above them.

Under the direction of William the Conqueror, was made a book, called Doomsday Book, containing a register of all the estates in England: and in his history we read an account of the curfew, and order for all people to put out their fires and candles at eight o'clock in the evening, which has been thought a badge of the slavery he imposed upon the Saxons; but this was practised in many other countries, and was deemed a necessary precaution in these turbulent ages.

The Tower of London was built in the reign of William the Conqueror. [end 34]

WILLIAM II.

1087

WILLIAM RUFUS WAS PASSIONATE AND RASH.

WILLIAM the Conqueror, at his death, appointed that his eldest son Robert should succeed him in the duchy of Normandy, and his second son William (who was his favourite) in the throne of England: Robert was not contented with this distribution, but his resistance was vain.

In the reign of William Rufus began the Crusades, that is, the expeditions of the Europeans for the conquest of the Holy Land: we are now in the dark ages, and though most of the European nations called themselves Christians, they knew very little about the matter: ignorance however is not inconsistent with zeal

: they were shocked when they considered that the country where the Great Author of their [end 35] religion was born, had lived, preached, done many wonderful works, and had at last suffered death, and the tomb in which his body had been laid, was in the hands of unbelieving Saracens, the followers of Mahomet.

Pilgrimages were the fashion of this age: the well-meaning, but uninstructed, people who then lived, were accustomed to address separate prayers to every saint in heaven; and these prayers were supposed to have the more merit, if they were said at the tomb, where the bones of the saint had been laid to rest: if any body had done a wicked thing the remembrance of which made him uneasy, he thought, and the priest encouraged him to think so, that if he made a pilgrimage to some celebrated tomb, or shrine, which was perhaps a hundred miles off, and especially if he went to it barefoot, the saint would prevail upon God Almighty to forgive [end 36] him his sin: it was the same way of thinking that induced them to whip themselves, to wear shirts of horsehair, and to make the naked stones their beds; they believed that, if they punished themselves, God would be satisfied and pardon them.

If the religious in this age made pilgrimages to the shrines of so many saints, you may think that they imputed a higher merit to a visit to Jerusalem, where Jesus Christ, the Saviour of the world, died, and was buried: the Saracens, from civilisation and refinement, and because the resort of Christian pilgrims brought wealth into their country, tolerated and accommodated them: but when, ten years after the Conquest, the Turks took Jerusalem from the Saracens, they treated the Christian pilgrims with rudeness and barbarity.

In resentment of this insolence, a [end 37] million of Christians joined from the different countries of Europe, and set out for the conquest of Jerusalem, which surrendered to their arms in the year 1099: Tasso, the best of the modern Italian authors, has written a fine poem on the subject.

Robert, duke of Normandy, was one of the commanders in this undertaking; and the better to enable him to raise his forces, he sold the government of his duchy during his absence, to William Rufus, for a sum of money. William Rufus, like most men of rank in this age, when amusements were so few, was very fond of hunting: one day when he was engaged in the pleasures of the chace in the New Forest, news was brought him that one of his barons in Normandy had taken up arms against his government: William was so enraged at what he heard, that he turned his horse's head, [end 38] and rode immediately to the next port; when he came there, the weather was cloudy and tempestuous, and the sailors were not willing to put to sea; William however insisted; he leaped into the vessel, and asked in a boastful sort of a tone, whether they had ever heard of a king who was drowned?

Another accident happened to him in the New Forest: Walter Tyrrel, one of his courtiers, was hunting with the king, and shot at a stag the arrow glanced against a tree, which changed its direction; it struck the king upon his breast, and he fell dead on the spot.

William Rufus built Westminster Hall, 200 feet long, for his dining-room: he had no children. [end 39]

HENRY I.

1100.

HENRY BEAUCLERC WAS AN EXCELLENT

SCHOLAR.

WHEN William Rufus was killed, Robert duke of Normandy was absent in the Holy Land: Henry, the youngest son of William the Conqueror, took advantage of this circumstance: he hastened from the New Forest to Winchester, where he got possession of the public treasure and thence to London, where he got himself crowned.

Robert hurried home, as soon as he heard of the death of William Rufus, and once more tried by the sword to gain the crown of England: but he not only failed in this, but soon after lost Normandy, where he had at first been gladly received: Henry took him prisoner, and put him in confinement, where he remained for the rest of his life, twenty-eight years. [end 40]

Henry Beauclerc had an only son, named William, whom he loved very much, but who was lost at sea at eighteen years of age. Henry was so affected at this event, that, though he outlived it fifteen years, it is remarked that he was never seen to smile afterward.

Henry had one daughter, Maud, married to Henry V, emperor of Germany.

STEPHEN.

1135.

STEPHEN OF BLOIS GOT THE CROWN BY A TRICK, BUT WAS HARDLY ABLE TO KEEP IT.

ENGLAND had never yet been governed by a queen; and some countries, France for instance, have always refused their sceptre to a woman; so Stephen, grandson to William the Conqueror by [end 41] a daughter, thought he would try his chance with the empress Maud: Maud was out of England, and Stephen got one of Henry's ministers to swear, that to his knowledge the king wished Stephen to be his successor: so Stephen was crowned.

By and by Maud came over with the army, and there was a great deal of fighting between her and her cousin: once she took Stephen prisoner; and twice she escaped being taken herself, the first time from Oxford by dressing herself in white, and walking at night over the snow, and the second time out of Wallingford in a coffin: at last it was agreed that Stephen should reign all the days of his life, and that Henry, son of the empress Maud by her second husband Geoffrey Plantagenet, should succeed him.

The fierce and haughty barons took advantage of the unsettled state of the [end 42] kingdom under Stephen, and built themselves each a strong castle for fortress to the number of eleven hundred and fifteen: thus they took all power into their own hands, and reduced the prerogative of the king to almost nothing: beside this, they were continually quarrelling and fighting with each other, so that poor England looked like a country of savages. [end 43]

THE

PLANTAGENETS.

HENRY II.

1154.

HENRY FITZ-EMPRESS WAS A MAN OF SPIRIT

AND SENSE, BUT WAS WHIPPED AT THE

TOMB OF THOMAS A BECKET.

HENRY Fitz-Empress was an extremely accomplished man: he first brought the art of writing poetry into England, after a lapse of two hundred years: French was still the language at court; and Henry encouraged Robert Wace

and Benedict St. More

to write long historical poems of the actions of his ancestors, dukes of Normandy before William the Conqueror.

Henry married Eleanor, heiress of Aquitaine, who brought a great addition [end 44; between 44-45 there is a page of four engraved portraits] to his territories in France: but she was a proud, ill-tempered woman, and led him a disagreeable sort of a life.

To console him for this misfortune, he attached himself to a very beautiful lady, called Fair Rosamond,

by whom he had several children: queen Eleanor was very jealous of her; and, as the story goes, the king made a bower for her to live in at Woodstock in the midst of a labyrinth, so contrived that nobody could find the way through it except they were in the secret; queen Eleanor got herself instructed, and went into the bower with a sword in one hand, and a bowl of poison in the other, and told Fair Rosamond that she might choose by which of them she would die; Rosamond took the poison and expired.

Henry had another great quarrel with Thomas à Becket: he saw how much the church in these dark ages [end 45] was disposed to domineer over the state, and how the popes made and unmade kings; and he set his heart upon remedying so disgraceful an evil.

The way it had grown was this: the pope of Rome, and the bishops and monks all over Europe, made a common cause, and agreed that whatever would add power to the one, would add power to the other: so that the popes of Rome acquired an authority, something like that of the emperors of Rome in the days of their prosperity, and had an army of priests and monks scattered in every quarter, who adhered as faithfully to their chief, as ever the body-guard of a sovereign did to the monarch who paid them.

Henry determined to break this league: he had a minister Thomas à Becket, who was exceedingly clever, and had never disobliged him in any thing: he thought, if he could once raise this [end 46] man to the highest dignity of the church in England, and make him archbishop of Canterbury, every thing else that he wished would follow of course.

You cannot think upon how familiar terms this able king and his clever minister lived with each other: one day as they were riding on horseback through the streets of London, they observed a beggar shivering with the cold: Would it not be a good action, said the king, to give that poor fellow a warm coat in this hard season? That it would, said Becket; and your majesty does well to think of such charitable actions: Then he shall have one presently, replied Henry, and with that, gave a smart pluck to Becket's cloak: the minister pulled it close about him, and defended himself as well as he could, till both king and minister had like to have been down in [end 47] the dirt: at length Becket, like a good courtier, let go his hold, and the king gave the cloak to the beggar: it was made of scarlet, and lined with ermine: the beggar knew nothing of the quality of the persons he saw, and was not a little surprised at the nature of the present.

Becket was as great a patron of learning as the king; and, while Henry encouraged the French writers, his minister contracted a strict intimacy with the best authors in Latin he could meet with: Joseph of Exeter, his friend, composed a very tolerable poem on the Trojan war,

and the prose of John of Salisbury is still admired for the age in which he wrote: Becket lived in a very splendid manner, and spent his leisure-hours in hunting, hawking and horsemanship: this man, for the reasons that have been mentioned, Henry made archbishop of Canterbury. [end 48]

Whether Becket gave any promises to the king I cannot tell, but if he did he certainly broke them all: he no sooner received this preferment, than he determined within himself the plan he would pursue: if he had answered the king's wishes, he would have been spoken ill of and hated by all the clergy of Europe; they would have called him a false brother, an apostate, a tool, and an atheist: this was by no means Becket's intention; he wished to be honoured, and not to be despised.

I suppose too Becket had some religious feelings concerned in the change that now took place: he thought that a courtier and a minister might take some liberties in his way of living, but that a different conduct was due from the first clergyman of a great country: according to the religious notions of those times, he laid aside all his pomp, wore sackcloth next to his skin, and fed [end 49] upon nothing but bread, water and herbs: he whipped himself often and severely, as a punishment for his sins; and, in imitation of what we read of Jesus Christ, washed the feet of a certain number of beggars every day: Thomas à Becket soon passed for the first saint in the land.

Henry, having thus, as he thought, secured himself a staunch friend in the head of the church, brought up a law to prohibit appeals to Rome, and other practices by which England was made dependent on the pope: who do you think was the principal person that opposed this measure? Thomas à Becket. He said, that he owed all manner of obligations and deference to the king, but that he could not betray the duties of his station; he would die sooner than yield: the quarrel grew hotter and hotter: the king seized all the arch- [end 50] bishop's estates, and Becket was obliged to fly beyond sea.

The pope and the king of France received Becket with great love, and determined to carry him through is difficulties: the clergy and a great part of the people of England thought the king acted very wickedly, in quarrelling with and banishing so good a man: Henry was obliged to submit: he gave up the law he wanted to establish: Becket and he met in Normandy, and seemed to be friends.

The king staid in Normandy, while Becket passed over in triumph to his palace and cathedral of Canterbury: Henry could not help muttering to himself what an ungrateful and troublesome subject he had got: a wicked, slave-spirited courtier overheard what the king said, and thinking to win his favour for ever, passed over to England with two or three followers, and mur- [end 51] dered Becket near the high altar in his own cathedral: every body was shocked: his death was the triumphant death of a martyr: thousands of miracles were said to be afterward worked at his tomb, and he was worshipped as the greatest of saints, as long as popery lasted in the island.

Henry could not otherwise make his peace with the pope, the king of France, and his own subjects blinded with superstition, than in the way before mentioned, by walking barefoot to the tomb of the holy man, and causing himself to be whipped on his naked back by monks of the cloister.

Poor Henry, unfortunate in his wife, unfortunate in his minister, was still more unfortunate in his children: he was on all occasions a warm-hearted man: he married for ambition, not for love, and therefore queen Eleanor of all persons perhaps had least reason to [end 52] to be pleased with him; but I have told you how kindly and familiarly he behaved to his minister; and he was a most affectionate father.

He loved his eldest son Henry so much, that he determined to admit him to a share of royalty in his own life-time: he made a fine coronation for him; and to do him the more honour, waited upon him at table, according to the manner of the feudal times: the good father could not help observing, as he did it, Never was prince more royally served! I see no such great matter in it, answered the ungracious youth, that the son of an earl should wait upon the son of a king.

Prince Henry afterward joined the king of France, his father's worst enemy, against his parent: queen Eleanor encouraged her two next sons, Richard and Geoffrey, to join in the rebellion, and they led their too in- [end 53] dulgent father a weary life: at length prince Henry died; but the others persisted in their disobedience, and the poor king thought he had no consolation left, but in his youngest son John, a graceless varlet, but who had the art to carry himself smoothly to his father: by and by the king discovered that John, with all his pretences, had acted in the basest and most treacherous manner:

The discovery broke his heart, and he died.

In the reign of Henry happened the conquest of Ireland, which was however rather nominal, than real: we gained the city of Dublin and a little province round it; but the greater part of the island continued in the hands of its native princes. [end 54]

RICHARD I.

1189.

RICHARD COEUR DE LION FOUGHT FOR THE HOLY LAND WITH THE SULTAN SALADIN.

TWO years before Richard came to the crown, the sultan Saladin took Jerusalem from the Christians, after they had possessed it ninety years: all Europe was astonished and confounded at the intelligence, and a new crusade was immediately fitted out for the recovery of the Holy Land: Richard, who burned with the desire of the military glory, was one of the commanders.

Of all the real histories of war, that of the war between Richard and Saladin is the most heroical: Richard performed feats of personal valour that are almost miraculous: Saladin (no Turk, but a Saracen

) was superior to Richard in generosity and civilised manners: Richard took Acre at the end of a three [end 55] years siege, and won a great battle against Saladin at Ascalon; but he was obliged to give up the war without taking Jerusalem: he made a truce with the sultan for three years: when he came away, he sent Saladin word that, at the expiration of the truce, he would not fail to give him again the meeting with more numerous forces; to which the sultan politely replied that, if it were his fortune to lose this portion of his dominions, he had rather it became the conquest of the king of England, than of any other prince in the world.

King Richard was shipwrecked near Venice on his return to Europe: as he had offended most of the princes who had joined in the crusade with him by his superior glory and the violence of his temper, he disguised himself like a pilgrim, that he might cross Germany safely by land: he was found [end 56] out however and arrested by the basest of his rivals, Leopold, duke of Austria, who threw him into an obscure dungeon at Dirrenstein on the Danube: for some time no one knew what was become of him: in this perilous situation Blondel, a minstrel, and a fast friend of king Richard who had been extremely fond of his heroic songs is said to have wandered among all the fortresses of that part of the world, to find where his brave master was hid: as he approached the castle of Dirrenstein, he struck of a favourite ballad, which he and the king had often sung together: when he had finished the first stanza, a voice from within the walls, which he immediately knew for king Richard's, began the second: I suppose Blodel found some means to letting his master know what he purposed: he then went immediately and informed queen Eleanor, the [end 57] mother of Richard: a great ransom was raised, and the king was finally brought home again to his country: he did not however long survive, being killed by an arrow, as he was besieging the castle of one of his rebellious barons in Normandy.

In the time of Richard lived the famous Robin Hood, who retired with a hundred followers into Sherwood Forest, where he lived upon the king's deer, and the booty he took from travellers: upon him four hundred men never dared to set, though ever so strong: he pillaged the rich, to give to the poor; so that of all thieves he is the prince and the most gentle thief: volumes of old English songs have been made of his exploits, some of which are printed, and called Robin Hood's Garland.

JOHN.

1199.

JACK LACKLAND WAS A PITIFUL FELLOW, AND DIED OF EATING PEACHES; IN HIS TIME WAS MAGNA CHARTA.

JOHN Lackland may challenge all history to produce his equal in folly, presumption, and wickedness: you have heard how he behaved to his father.

The true heir to the crown on the death of king Richard, was Arthur of Britanny, the son of Geoffrey, John's elder brother: Richard however made a will bequeathing the succession to John; and the barons of England admitted his claim: Arthur was twelve years old at the decease of Richard, and four years after fell into the hands of his barbarous uncle, who put him to death; according to some accounts stabbed the defenceless youth in a [end 59] boat in the night-time with his own hand.

The king of France, seeing how foolish and wicked a prince John was, thought this a favourable time to take away Normandy, and unite it to his own crown, and he succeeded; when John heard of it, he said, What the French conquer in years, I will retake in a day, when I set about it: but John was all talk, and no performance.

John quarrelled with the pope, and for some time swore, and blustered, as was his custom, and boasted what great things he would do, but afterward submitted: he confessed himself the subject of the pope, and delivered his crown into the hands of the pope's legate, who kept it five days before he returned it.

Every body took advantage of John's want of character and spirit: they cared nothing for his blustering: the more [end 60] he vapoured, the more sure they were he would come down: the barons of England joined together, and drew up Magna Charta, a declaration of the rights of the free people of England,

which they forced John to sign at Runny Mead, near Windsor: till his time, as all the Norman kings had been soldierly and active men, they governed as much as they could by their own will, and endeavoured to shun any such declaration as is contained in Magna Charta.

John had no sooner signed Magna Charta, then he showed an inclination to break it; the barons, tired of his wickedness and tyranny, invited over Louis, the dauphin of France, who soon took possession of London, and all the southern part of the kingdom: nothing but the death of John at this crisis, prevented his entire success.

Among the other extravagances of [end 61] John, he is said to have sent a proposal to the Miramolin, or emperor of Morocco, offering to turn Mahometan, if the Miramolin would aid him against the pope, the king of France and the English nation.

King John is the name of the most ancient of Shakespear's historical plays: it contains many fine scenes respecting the unfortunate Arthur, and various considerable events of this reign: in general the productions of this incomparable author are the best Guide to the History of England, as far as he has treated upon the subject. [end 62]

HENRY III.

1216

HENRY OF WINCHESTER WAS A POOR CREATURE, AND HAD A TROUBLESOME REIGN OF FIFTY-SIX YEARS.

THERE are four kings in the series of English monarchs, who laboured under an evident want to capacity; these are Henry of Winchester, Edward of Caernarvon, Richard of Bourdeaux, and Henry of Windsor: Henry of Winchester was the only one of the four, who died a natural death.

Henry was only nine years old, when he came to be king: William Marshal, earl of Pembroke, was appointed lord protector of England during his childhood, and under Pembroke's able administration the French invaders were driven back to their own country.

The most famous statesman in the reign of Henry of Winchester was Si- [end 63] mon Montfort: Henry reigned, comparatively with little interruption from his barons, for forty-two years: they at length grew tired of his insignificance and imbecility; and Simon Montfort being at their head, he possessed for seven years more authority in the realm than the king.

A great change had taken place in Europe since the time of William the Conqueror; during his life all the people of Christendom were either soldiers, or clergy, or husbandmen: the whole were divided into lords and slaves: there were few artists and less trade: the crusades were the first cause that gradually produced a new face of things: they gave birth to an intercourse between distant nations, through the means of which men learned new wants and new accommodations: we imported learning and luxuries from the East: Europe kept possession of the kingdom [end 64] of Jerusalem for ninety years: and the towns of Italy first, and afterward of other countries, became rich in merchandise by means of their traffic to Jerusalem.

The citizens and merchants were neither lords nor slaves: about the same time there arose a middle set of men in the open country, persons who held land as freemen, and yet were not rich enough, to associate with the barons, and frequent high courts of parliament: all this gave rise to a their order of persons in the kingdom; burgesses were elected to represent the towns, and knights of shires to represent the inferior landholders: Simon Montfort was the author of the house of commons, that precious part of our government, in England.

Two great battles were fought between Simon Montfort and Henry of Winchester, the first at Lewes, here [end 65] king Henry was taken prisoner, the second at Evesham, where Simon Montfort was killed: Henry spent the short remainder of his days in peace.

Henry of Winchester was a great encourager of the fine arts of architecture, painting and sculpture: the beginning of these arts were rude, but the period of Henry III is considered as the dawn of taste: he rebuilt Westminster Abbey from the ground.

From his reign we may also date the commencement of literature and science in modern times: Friar Bacon in particular was a wonderful man, to whom the art of making gunpowder, telescopes and microscopes was familiar, centuries before they were brought into ordinary use.

[end 66]

[pp 66 is a set of four engraved portraits]

EDWARD I.

1272.

EDWARD LONGSHANKS WAS KNOWING AND WISE, BUT HE LOVED WAR, AND CONDUCTED IT BARBAROUSLY.

THE two kings in the English history who possessed the greatest portion of understanding and genius, were William the Conqueror and Edward Longshanks.

Edward, at the same time of his father's death, was engaged on a crusade to the Holy Land.

There is an agreeable story of Edward, that while he was in the Holy Land, a Mahometan assassin came into his tent to murder him, that he stabbed Edward in the arm with a poisoned dagger, and that queen Eleanora saved her husband by sucking the poison out of his wound: certain it is that Edward was passion- [end 67] ately fond of Eleanora all the days of her life.

Edward Longshanks introduced the old Roman law, commonly called the civil law, into England, and spread over his country a face of security, propriety and order, which has never since been banished from it.

As he was a prince of extensive views, he aspired to reduce the whole island under one rule, and regarded that as the natural means of giving to the English people a permanent stability and independence of all the nations of the earth.

The Welsh, calling themselves the Ancient Britons, had continued unsubdued ever since the retreat of the Romans; they had been unconquered by the Saxons and the Danes: the Norman and Plantagenet princes had frequently been at war with them, and obliged them to pay tribute, but they had still [end 68] been governed by princes and laws of their own: Edward Longshanks completed the conquest of Wales.

From the time when the Romans flourished in Britain, the Welsh had been Christians: the Druidical religion and learning had irretrievably perished: but there was still a class of men among the Welsh called the Bards: these were such an imperfect image of the great masters of astronomy and history in the Druidical times, as could be expected to be preserved through centuries of ignorance, calamity and popish superstition: still they had songs, dear to their countrymen, which preserved among their hearers the love of Wales and of liberty.

Edward, who wished England and Wales to be for ever united, did not love the Bards: there is a story that he invited a general assembly of them to meet him at Conway, and there caused [end 69] them all to be murdered: Gray, a late English poet, has written an ode of some merit on this subject:

ever since the conquest of Wales by Edward I, the eldest son of the king of England has been called prince of Wales.

An event occurred soon after, which gave Edward a favourable opportunity for interfering in the affairs of Scotland: the male line of the kings of that country had become extinct, and disputes had arisen between John Baliol and Robert Bruce, descendants of the female line, which of these had the best claim to the crown: Scotland was on the eve of a civil war on the subject; when the wisest heads in the government of that country, advised that Edward, famed for knowledge and sagacity, should be called in as umpire to settle the dispute, and that all parties should swear to abide by his decision.

Edward set out in execution of this [end 70] office with an army for the borders of Scotland: and, when he had got every thing into his own hand, he set up a barefaced and groundless pretence, that the kings of Scotland had been at all times feudal vassals under the kings of England, and required the candidates to swear this subjection, before he would decide upon their claims: Edward had every advantage over the country without a government or a king, and they were obliged to submit: he then decided in favour of Baliol, the descendant of the elder branch of the royal family of Scotland.

It was not that he might add a feather to the English crown, that Edward asserted the vassalage of Scotland: he soon picked a quarrel with the new king, and asserted that he had not performed all the duties that were required from the feudal vassal to his superior: he therefore, declared the vassal state for- [end 71] feited to the lord paramount, and marched an army to take possession of it: in this enterprise he succeeded.

All nations love their independence, and abhor the idea of becoming a province and an inferior member of some other nation: it is the name of ENGLAND, that has inspired our soldiers and sailors with bravery, and our poets with sublimity and imagination: Scotland is not less dear to a Scotchman: when a country is no longer its own master, it loses its peculiar name, or that name no longer excites the same glow in the bosoms of its natives.

The officers that Edward sent to manage Scotland, governed it tyrannically: one of the bravest and noblest of mankind, sir William Wallace, arose at this time to rescue her from subjection: he underwent incredible hardships, and achieved wonders: but his successes were not permanent: he was at last betrayed into the hands of Edward, who basely caused him to suffer the death of a traitor on Tower Hill: there is an old poem, as long as Homer's Iliad, in the Scotish dialect, by a person known by the name of Blind Harry, commemorating the achievements of sir William Wallace.

Three times Edward conquered Scotland: a third time it rebelled; and, having been now some years without a king, the Scots chose Robert Bruce, the grandson of the competitor of John Baliol, for their sovereign: Edward marched against Bruce, but died on the road, in the sixty-ninth year of his age.

Edward, like his ancestors, the Plantagenets, was a patron of literature and the poets: in his reign Oxford had at one time thirty thousand students, a much greater number than at any subsequent period. [end 73]

EDWARD II

1307.

EDWARD OF CAERNARVON, A WEAK PRINCE, WAS GOVERNED BY UPSTARTS, AND CRUELLY MURDERED BY HIS WIFE IN BERKELLY CASTLE.

THE death of Edward I was a fortunate event for the Scots: they kept their ground and in the seventh year of the reign of Edward of Caernarvon, won a decisive battle at Bannockburn over the whole strength of the English nation: an exquisite song on this battle has lately been produced by Robert Burns, the Ayrshire ploughman.

Edward of Caernarvon had attached himself while a boy, to an adventurer, by name Gaveston, and when he came to the crown, gave the government of the kingdom into his hands: Gaveston was a handsome man, expert in youthful sports, riding and fencing; but he was [end 74] vain, conceited and overbearing: the old nobles of the kingdom could not endure him: they obliged the king to send him into banishment: but, finding that neither the king nor Gaveston minded his promise, and that, as soon as the barons had gone home, Gaveston was restored to as much power as ever, they at length struck off his head without form of trial, on a hill near Warwick.

Edward of Caernarvon could not live without a favourite, and after the death of Gaveston attached himself to a young man of the name of Spencer: he was not of low rank like Gaveston: he was the son of a respectable nobleman, though not of the highest class: but the barons no sooner saw him fixed in power, than they hated him as inveterately as they did his predecessor: Spencer was finally hanged on a gibbet, together with his venerable father near [end 75] ninety years of age, in defiance of law, decorum and humanity.

The wife of Edward of Caernarvon was Isabella, sister to the king of France: she had long despised her husband, and wished to govern him; but she was never able to gain his confidence: at length she forgot herself so far as to live in open adultery with Roger Mortimer earl of March: one crime led to another: she who had first despised, and next proved unfaithful to her husband, afterward deprived him of his crown, and then of his life.

EDWARD III.

1327.

EDWARD THE THIRD WAS THE CONQUEROR OF FRANCE

EDWARD the Third was fifteen years old when his father was murdered [end 76] and three years after, he joined in a confederacy with certain noblemen, who entered Nottingham Castle where the queen and Mortimer lay, seized Mortimer, who was tried and hanged for his crimes, and sent Isabella to prison.

The reign of Edward III belongs to the age of chivalry: the first idea of chivalry was for a knight in complete armour to sally forth on horseback in search of adventures, to succour distress, and punish oppression: in ages of the world, when every baron had a castle, and there was no king or law strong enough to prevent him from doing what he pleased, such a practice was useful: men who can do what they please, will often please to do what is wrong.

In the stories of the knights-errant, or the knights of chivalry, we continually read of their rescuing ladies from [end 77] dungeons and tyrants: a lawless, uneducated man, who was lord of a castle too often would not be at the trouble to court the lady he liked, but ran away with her by force, without asking her own consent or that of her parents and then, if she was angry, would shut her up in a dungeon, till she consented to whatever he pleased: the knight-errant, when he entered on his profession, vowed that he would devote all his powers to the service of God and the ladies.

By the time of Edward III the real use of chivalry was pretty well over but it had in it certain features of courage, refinement and humanity, they made it continue a favourite: when the knights no longer rode out to encounter an oppressor (or, as we find it in story-books, a giant or a dragon he dressed himself in armour, mounted on horseback, and invited any other [end 78] [n.b., image of jousting between 78 and 79] knights he could meet with to a friendly trial of skill: when a great many met together for this purpose, it was called a tournament.

There were more tournaments in the reign of Edward III, than in all the rest of the English history put together: the king was frequently one of the combatants, and the queen and all her ladies, seated upon thrones and lofty benches in a circle, were among the spectators.

As Edward was very fond of splendour and show, and a great encourager of tournaments, he was led naturally from this image of war, to wish for the reality: like too many other kings and heads of nations, he desired to be a conqueror.

A conqueror is a man who sallies forth at the head of an army, to disturb the peace and repose of honest, unoffending husbandmen, peasants and ar- [end 79] tisans: he causes the death of thousands, and reduces nations to slavery, that he may become famous, and have songs made in his praise.

Edward III found that, in right of his mother, he had a claim to the crown of Frances, and that it might admit of a dispute whether he was nearer to the inheritance, or the Frenchman whom the French nation chose to have reign over them: he therefore collected a great army, and set out for the conquest of France: if he succeeded, he thought he should be one of the most famous personages in history.

If he had succeeded, he would have fixed the seat of his government at Paris, because France is a much larger and more populous country than England; and England would have become a poor dependency of the French throne.

At first Edward made but a very small progress; after some years he got into a desperate situation, at a place called Cressy: his army was nearly made prisoners: the English warriors were very brave: they fought their way through; they defeated the French, and won at Cressy a memorable and astonishing victory: this however was not the end of the war.

Edward III had a son called Edward the Black Prince, because he wore a suit of black armour: he was one of the most accomplished warriors that ever lived: ten years after the battle of Cressy, he got into a similar difficulty to that of his father on the former occasion, and extricated himself from it with the same success: he took John, king of France, prisoner: the battles of Cressy and Poitiers are two of the most famous victories in modern history.

When the Black Prince had made [end 81] king John prisoner, he seated him at a splendid entertainment in his tent, and himself waited behind the king's chair: this was in the very manner of the institutions of the feudal system, and of chivalry: when he brought king John over with him to London, he mounted his royal prisoner on a beautiful white horse of a large size, and rode a small black palfrey beside him along the streets: this was a much nobler spectacle than a Roman triumph, where the conqueror dragged his captive king as so many melancholy victims at his chariot-wheels.

There is a famous story of the siege of Calais by Edward III: the brave inhabitants held out for nearly a year: they surrendered at last from the pressure of hunger only: they asked for no more than their lives: Edward was determined to punish them for their honourable adherence to their duty: at last he said, if they would send six of their principal citizens to him, in their shirts, with halters about their necks, he would forgive the rest.

This was a more cruel difficulty than before: where were six citizens to be found, who would go voluntarily to death, to save the rest? at last an admirable fellow, Eustache de St Pierre, offered himself

: five others followed his example: it is said, Edward III would have put these generous fellows to death, if his queen Philippa had not fallen upon her knees before him, and obtained their lives: how strange that a prince who behaved so humanely to people of rank, should have been so harsh and unrelenting to honest citizens!

Edward III lived to sustain the loss of all his conquests: he grew old: the Black Prince was seized with a consuming disorder, which robbed him of all [end 83] power of exertion: the English generals did their best, but in vain: France recovered her independence and prosperity.

In the reign of Edward III lived Chaucer, the first, and one of the greatest of the English poets: the English language in his time recovered its ascendancy: the poets who had hitherto been patronised by the Plantagenet princes were French: but the descendants of the Saxons were always much more numerous in England than the Normans, and the language of the multitude at length gained the superiority: it is Chaucer who has presented to us the first genuine model of the present language of England.

Edward III was the builder of Windsor Castle: the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge also began to be founded in this reign. [end 84]

RICHARD II.

1377.

RICHARD OF BOURDEAUX WAS ADMIRABLE WHILE A BOY, BUT CONTEMPTIBLE WHEN HE GREW TO BE A MAN: HE WAS DEPRIVED OF HIS CROWN, AND STARVED TO DEATH IN PROMFRET CASTLE.

IN the dark and barbarous ages the lower people were slaves: there was such a thing as liberty in England and other European countries; but it was confined to the lords and holders of estates.

I have told you how the commons, by means of the progress of trade and good sense, rose in process of time to a certain importance: still however the greater part of the country people were slaves: as much had been obtained, they naturally wished for more: first in France, and afterward in England and other countries, they rose in arms, and demanded those privileges which [end 85] might best conduce to their improvement and comfort.

The occasion of the insurrection in England was a poll-tax, or a tax of so much a head, upon all the inhabitants of the kingdom: the collectors of the tax behaved very brutally: an act of indecency that they allowed themselves in to the daughter of a mechanic, named Wat Tyler, exasperated the father of the girl, who, with the hammer that was in his hand, killed the ruffian: thousands were already in a rage against the tax, the action of Wat Tyler

served them for a signal, and they flew to arms.

When the common people have got arms in their hands, and feel themselves masters, they are apt to run into the most outrageous excesses

: the insurgents marched for London in an immense multitude, burned down the Temple, and the Monastery of St John [end 86] in Smithfield, set open the prisons, and cut off the heads of the archbishop of Canterbury, the lord high treasurer, and many other persons of distinction, merely out of envy to their rank.

Richard of Bourdeaux, son of Edward the Black Prince, was at this time only fourteen years and a half old: it was however thought necessary that he should go out from the Tower where he resided, and parley with the rebels in Smithfield: what they demanded was their liberty: during the conference, a quarrel arose between Wat Tyler and a knight attendant upon the king: Walworth, mayor of London, took part with the knight, and felled Tyler to the ground: the multitude grew furious: at this instant king Richard rode forth from his own people to meet the rebels: he called out to them to follow him who was their king, and he would grant them whatever they [end 87]should require: he led them into the open fields: while they were debating on terms with him, a considerable military force was collected: the multitude lost their opportunity, and in the insurrection was soon after suppressed, and rigorously punished.

Richard, as he grew up, appeared to be one of our weak sovereigns, who could not live without a favourite: the name of the man he chose was Vere, earl of Oxford, descended from the ancient nobility: but like most favourites, he was forward, presumptuous and overbearing: Richard himself was a mere man of pleasure, fond of the pomp and magnificence attendant upon royalty, but careless of its duties: his expences were lavish and prodigal, and excited a general sentiment of discontent.

Thomas of Woodstock, one of Richard's uncles, and brother to the Black [end 88] Prince, took advantage of his nephew's feeble character and unpopularity, drove the favourite into banishment, and usurped all the powers of royalty, leaving Richard nothing but the name.

This lasted three years, when a second convulsion restored Richard to his authority, under the guardianship of a new set of favourites, by whose orders Thomas of Woodstock was smothered in his bed.

Richard gained little by the murder of Thomas of Woodstock: the next year Henry of Bolingbroke, son of the famous John of Gaunt duke of Lancaster, another of Richard's uncles, raised an army against the king, took him prisoner, shut him up in Pomfret Castle, where he caused him to be starved to death, and placed himself on the throne.

In the time of Richard of Bourdeaux lived John Wicliffe, a man of great [end 89] learning and courage, who preached against the abuses of popery

: his followers were numerous, and some of them of high rank, but his party was finally suppressed: Wicliffe first translated the Bible into English.

The reign of Richard of Bourdeaux is the subject of the second of the series of plays, which Shakespear has founded on the history of England.

[end 90; page 91 blank] […] true heir, he could not feel easy in his ill-gotten dignity.

The whole reign of Henry of Bolingbroke was infested with plots and conspiracies to restore the true heir: the most distinguished leader in these hostilities was the famous Henry Percy, surnamed Hotspur.

Henry of Bolingbroke experienced another vexation: his eldest son Henry of Monmouth, appeared to turn out an abandoned libertine: he kept low company, was engaged in disgraceful riots, and even went so far with his licentious associates, as to rob on the highway.

King Henry, wasted and broken-hearted with perpetual griefs from without and within, died of a worn-out frame, at the age of forty-five, after an uncomfortable reign of thirteen years. [end 92]

Shakespeare has written the reign of Henry IV.

HENRY V.

1413.

HENRY THE FIFTH WON THE BATTLE OF AGINCOURT ON ST. CRISPIN'S DAY.

HENRY, surnamed of Monmouth, to the astonishment of every body, laid aside his riots the moment he came to the crown, and ever after behaved himself in such a manner as to gain the affections of his subjects.

The reign of Henry V was splendid; but those very circumstances which constitute its splendour, are in the eye of reason its deepest disgrace.

The king of France was seized with madness, yet a madness that had inter- [end 93] vals: his courtiers and the princes of the blood-royal, were ambitious and profligate: these circumstances involved France in the most terrible calamities: Henry seized this occasion to revive the claim first set up by Edward III, of the royal line of England to the throne of France.

He won the battle of Agincourt, under circumstances exactly similar to the battles of Cressy and Poitiers: with a small army, he seemed to be surrounded and cut off by the numerous forces of France: he forced his way through them, and obtained the fullest and most entire victory.

It was not the battle of Agincourt that placed Henry V on the throne of France: he did not fully carry his point till five years afterward, when, having a second time crossed the seas with an army, such were the distractions of that unhappy country, that he [end 94] was able to dictate what terms he pleased: he graciously permitted the reigning sovereign to retain the title and state of a king, but took the government into his own hands, and decreed that, whenever the present king should die, he himself and his heirs were to succeed to the throne.

Shakespear had written the history play of Henry V.

HENRY VI.

1422.

HENRY OF WINDSOR, HALF-MADMAN, AND HALF-FOOL, LOST THE CROWN THAT HIS GRANDFATHER HAD WICKEDLY SEIZED.

THE king of France died in less than two months after his conqueror; and Henry of Windsor was proclaimed king of England in London, and king of France in Paris, before he was a year [end 95] old: he lived long enough to become a poor and friendless prisoner in the Tower of London.

The son of the late king of France still maintained some authority in the southern parts of that kingdom: war was carried on for seven years between the contending parties, but the balance of success was in favour of the English: at the end of seven years their enemies appeared ruined: the last trial of strength was before the town of Orleans besieged by the English.

When every thing now looked desperate for the French, a poor young woman, twenty-seven years of age, the maid-servant of a village-inn, called Joan of Arc, came to the prince-dauphin of France, and told him she was inspired by God to raise the siege of Orleans, and to place him on the throne of his ancestors: in the now wretched state of his affairs the prince [end 96] thought any means worth trying: the defeated and unhappy French believed every thing Joan of Arc told them: she put herself at the head of a detachment, and forced her way into the town: the English were as much astonished as the French, at the appearance of this strange sort of general: the siege was raised.

Joan of Arc conducted her sovereign to the cathedral of Rheims in the northern part of the kingdom, where all his ancestors had celebrated their coronation, and where the same ceremony was now performed for him: this was the last of her exploits: she was soon after taken prisoner by the English, who barbarously caused her to be burned alive for a witch: they never however recovered the effects of her achievements, and were finally driven out of France.

This is the first part of the history [end 97] of Henry of Windsor: during the early part of his reign he fought for the crown of France; during the later he was obliged to fight for the crown of England.

John of Gaunt duke of Lancaster was the third, and Edmund of Langley duke of York the fourth son of Edward III: but the descendants of York intermarried with the Mortimers' claim to the throne of England: this was the source of the famous wars of York and Lancaster, frequently called the wars of Two Roses, White and Red.

The mischiefs which the English had inflicted upon France, now recoiled upon ourselves: our king became mad with a madness exactly similar to that of the late king of France: his government was not less weak, and distracted with factions; and Richard duke of York [end 98] was appointed lord protector of England during the king's indisposition.

Henry VI had for his queen, Margaret of Anjou, a lady of great beauty, understanding and accomplishments: this woman for a long time supported the party of Lancaster by her abilities: she had borne to king Henry an only son, a child of great promise, and it was to the maintaining his claim to succeed after the death of his father, that she directed all her exertions.

Richard duke of York, lord protector of the kingdom, had a better claim to the crown than he who wore it: this was a critical situation: queen Margaret thought it dangerous to suffer him to retain his office: he seemed to aspire to nothing more, but he would not part with what he had got: both sides had recourse to arms: after his second victory over the Lancastrians, and having twice taken king Henry [end 99] prisoner, duke Richard caused the parliament to confirm him lord protector during the life of Henry, and heir to the crown after his decease.

Margaret having raised new forces in the north, the battle of Wakefield was soon after fought: in this battle the Yorkists were defeated, and duke Richard killed.

Eton college, the most celebrated school in England, was founded by king Henry VI.

Shakespear has described the principal events of this reign in three historical plays, called the First, Second, and Third Parts of the Reign of Henry VI.

THE

HOUSE OF YORK.

EDWARD IV.

1461.

EDWARD THE FOURTH WAS AN ARRANT LIBERTINE, AND TOOK AWAY THE FAMOUS JANE SHORE FROM HER HUSBAND THAT SHE MIGHT LIVE WITH HIM.

EDWARD, eldest son of Richard duke of York, was daring and adventurous, and in a short time after the death of his father, caused himself to be proclaimed king by the title of Edward IV.