When, in October 1834, Dorothy Wordsworth began what would prove the last volume of her Rydal Journals (RJ), she already seemed on borrowed time, having repeatedly been on deathwatch since falling seriously ill in April 1829. Her survival was, in part, a testament to the devoted care of her physician, Thomas Carr, and her family, including her brother William, whose daily routine in 1833 included reading to her, massaging her swollen feet, and, weather permitting, wheeling her into the garden (fig. 1).

While Dorothy’s condition was no longer critical during the six-month span (October 1834–April 1835) at the center of Notebook 15, she remained largely confined to her upstairs bedroom at Rydal Mount.

Figure 1. John Harden, Dorothy Wordsworth in a Wheelchair (pen and ink on paper, 25 August 1842). The artist, a longtime friend and neighbor of the Wordsworths, wrote beneath this sketch, Recollection of Jessie’s & my visit R[yda]l M[oun]t & interview with poor Miss W—. The Jessie who accompanied him was not his wife (who had died in 1837) but his youngest daughter. (Courtesy: Lakeland Arts/Bridgeman Education)

The prevailing norm for interpreting—or, perhaps more accurately, disregarding—the two decades between the close of the RJ in 1835 and Dorothy’s death in 1855 was established by Ernest De Sélincourt in 1933, when he asserted that “the last twenty years of posthumous life . . . only belong to the biography of Dorothy Wordsworth in so far as they reveal in fitful gleams something of what she once had been.”

While subsequent biographers have devoted more space to diagnosing Dorothy’s medical condition—variously speculating that suffered from gallstones, arteriosclerosis, “pre-senile dementia of a type similar to Alzheimer’s disease,” or “depressive pseudo-dementia, a condition in which severe depression mimics the symptoms of dementia.”

—they have largely followed De Sélincourt’s lead in taking the period covered by Notebook 15 as a harrowing transition into Dorothy’s “posthumous life.” With growing sensitivity in literary studies toward ageing and disability, however, this pattern might be changing. Polly Atkin’s recent book Recovering Dorothy (2021), in particular, offers an overdue corrective to the longstanding impulse to dismiss her final decades. Noting how “Dorothy Wordsworth’s biographers have had a peculiar predilection for killing her long before her death,” Atkin sets out “to shine a light into the darkness and restore the rest of Dorothy’s narrative.” Quite simply, she insists, Dorothy “did not die, emotionally or otherwise, until 1855. She did not vanish. She was not undone. She may have changed, as we all do, in sickness and in health, but she was still Dorothy.”

Of course, there is no disputing that Dorothy’s health was never again as robust after she was stricken with cholera or some other disease in early 1829; and, if read in isolation, Notebook 15 might be taken as proof of her gradual physical and mental decline. Shaky handwriting, ink spills, crossings-out, and basic errors proliferate as the volume draws to a close, and signs of what seems an increasingly circumscribed and dreary existence appear at every turn. On the “dull, dark & cold” tenth day of February 1835, for instance, Dorothy writes, “My limbs unusually weak. With difficulty I went to window & back.” A month later, on 15 March, she laments, “The greatest evil attending my present disordered state is that I can read or work little or none.” For every simple pleasure, such as her “companion Robin,” the bird who frequents her windowsill throughout the autumn of 1834, there seems a counterbalancing threat, like the new cat at Rydal Mount that leaves Dorothy in terror about the bird’s safety.

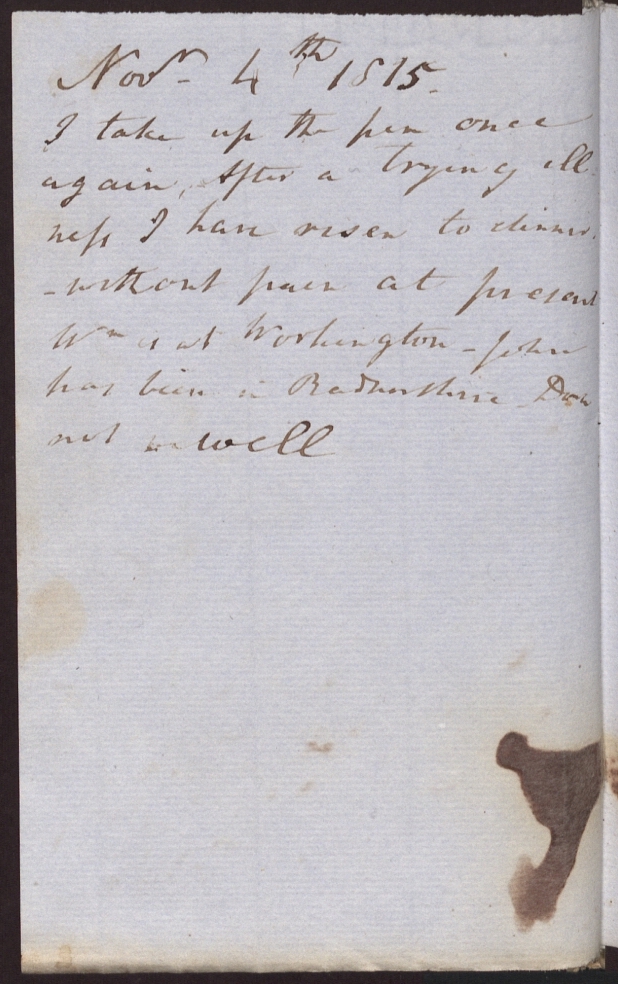

Seemingly further support for a narrative of steady decline comes in Dorothy’s concluding entry of 4 November 1835. Since having last written in her journal on 19 April, she had grown too “dreadfully weak and languid” to write, and her mental health had further plummeted after the shock of Sara Hutchinson’s sudden passing on 23 June.

Yet, resolved to return to her decade-long habit of recording her daily activities, she “[took] up the pen once again.” The pathos of the final entry that follows emanates, in part, from its inaccuracies—she gives the year as 1815 (not 1835) and seems to have been confused about her nephew John’s recent whereabouts—and also from its ending with the double negative “Dora not unwell,” as if asserting that to be “not unwell” is all one might reasonably hope for in this life (see fig. 2). The most heartbreaking aspect of this entry, however, is its isolation on the journal’s last page, as, after having mustered the strength to resume her journal, Dorothy could eke out but a single entry before needing to set it aside for good.

Figure 2. The final entry in Notebook 15 (Courtesy: Wordsworth Trust)

Writing in his own journal two months later, Dorothy’s friend Henry Crabb Robinson would attest to the severity of her physical decline. Two years had passed since Robinson’s last visit to Rydal, and he was obviously rattled to find on 2 January 1836 that, even in what was said to be “her best state,” Dorothy paid little heed to his presence and “went on repeating without intermission fragments of poetry—her brother’s, Cowper’s, Dr. Watts’s—then repeating the Doxology, and the most melancholy act of all, carried away by the association of ideas, repeating the Amen in a loud tone and mocking a clerk accompanied by loud laughter.”

Were one to stop reading there, this might seem unimpeachable proof of her ongoing deterioration; but continuing just a few pages further, we find Robinson rejoicing on 31 January at having found her “much calmer and reasonable.” Dorothy “sang some of her brother’s poems,” he reports, and “she evidently knew me, and was not irrational in anything she said.”

That this was not merely a momentary rebound is suggested by a remarkably lucid and witty letter that Dorothy sent Christopher Wordsworth Jr. a few weeks after Robinson’s visit. Playfully greeting her 28-year-old nephew as a “public Orator” often summoned “to speak in the presence of Kings, Princes and Bishops,” she explains she is writing because Christopher’s “uncle, the Poet of the Lakes, has been deputed” to speak at the groundbreaking for a new seminary, but “alas! the poet is no Orator and he knows not what to say on this important occasion.” Rushing to her brother’s aid, she merrily entreats her nephew, as “the first Orator of the Nation,” to “make a speech for [William] which I will answer for it he will pronounce verbatim.” Dorothy concludes by announcing her intention “to see you all at Cambridge in summer,” sanguinely reporting, “I have got through a mighty struggle, and thank God am now as well as ever I was in my life except that I have not recovered the use of my legs. My Arms have been active enough as the torn caps of my nurses and the heavy blows I have given their heads and faces will testify.”

Clearly, then, as Pamela Woof has written, “even in these final years there was more than imbecility to Dorothy Wordsworth; there are glimpses of what De Quincey calls her ‘very originality’ . . . in the later letters, verses and journals.”

Recognizing as much offers an important check upon any temptation to reduce the whole of Notebook 15 to a tale of her physical and mental slide. It invites us to balance Dorothy’s recurring complaints over the deaths of several dear friends, her own debilitating maladies, and dispiriting political news from Westminster with other moments when she exudes her trademark optimism and zest for life. The series of entries she wrote as 1834 rolled over into 1835, for instance, are among the most affecting and exuberant in the whole of the RJ. In her entry for 30 December, she describes how “Wm came to me rejoiced to hear thickly pattering rain after so long a pause – I could not but feel a touch of sympathy with him in remembrance of many a moist tramp; but sh[oul]d have been better pleased with bright moon & stars, & our late splendid evenings & mornings.” Two days later, after noting the “Lovely sun-rise & set,” she rhapsodizes, “Never surely in the 63 years that I have lived can there have been such brilliant New-years & Christmas days.” And, in the same elevated strain, she writes on 2 January, “Another year begun! and what a brilliant sun-rise – Oh! that men’s hearts could be softened! – then elevated by the goodness & beauty of all that is done for & spread before us!”

Elsewhere, Notebook 15 paints a portrait of long days and nights in a sickroom, where, when well enough, Dorothy read newspapers and religious books, made rugs for friends, and welcomed visits from well-wishers. While the entries at the start of this volume show her reading voraciously, her stamina had waned by February 1835 to the point that she had become reliant on her goddaughter (and regular companion) Ebba Hutchinson reading to her aloud. Wary, no doubt, of the addiction that had plagued her friends Coleridge and De Quincey, Dorothy took to assiduously logging each time she opened a new bottle of laudanum, and—in what should prove a remarkable trove for historians of medicine—she details treatments including the bleeding and blistering regimens endured by her niece Dora and her own use of Morrison’s Pills, arrowroot biscuits, and divers concoctions prepared by her faithful attendant Mr. Carr. Especially amid the political tumult surrounding the general election of early 1835, Dorothy’s mood seems to have risen and fallen depending of how successful the Tories had been in staving off Whig offensives. Such is the case near the end of Notebook 15, when, in her entry for 30 March 1835, she initially expresses pleasure that the Wordsworths’ new neighbor Dr. Thomas Arnold would be bringing to his family to the Lakes for Easter before remembering that the last visit of this “active zealous Doctor” had been “to vote for a Destructive Member” in the parliamentary election—a trip that, as she wryly and triumphantly notes, was “Happily not successful.”