Any discussion of teaching the Romantic with the contemporary will necessarily invite questions about the relative value accorded to each of the literary historical periods being brought into relation. Are we introducing contemporary texts (or debates or images) into our classrooms in order to “sell” Romanticism (to make it appear more relevant; more interesting; more, in our common-but-unfortunate parlance, “sexy”)? And is this type of appeal, arising out of a well-intentioned attempt to maintain a space for Romanticism in our curricula, misguided? (That is, are we merely reinforcing the secondary status we’re attempting to correct for?) Will comparisons between contemporary and Romantic texts always remain superficial? Does a presentist approach to pedagogy depreciate the texts under study by undermining their historical specificity? Might we, on the other hand, be giving the false impression that contemporary phenomena are simply a given and only distant historical phenomena are worthy of intensive analysis? I won’t be able to address all of these questions here—not least because I don’t think I have all of the answers to them—but these are the kinds of questions that inform the present essay.

I’ve been tempted to call my contribution to this special issue a defense of “relatability”: a persistent pedagogical bugbear that has of late been challenged, to widespread acclaim, in the popular press as well (see Mead and Onion). The idea that literature should be “relatable,” critics argue, is symptomatic of an epidemic of narcissism, evidence of a prevailing cultural aversion to difference. The ubiquity of the selfie (casual but posed self-portraiture, usually shared on social media) is often taken to be emblematic of this millennial penchant for naval-gazing. While I remain ambivalent about the term “relatability,” I have to admit that it’s true: I am defending the impulse to relate as a far more complex and generative response than these critics suggest. More importantly, though, I hope to offer an argument toward using relatability, especially when teaching the novel (the genre that has, since its emergence in mid-eighteenth-century Britain, been seen as most susceptible to this sort of response). The idea that literary texts (and, more precisely, literary characters) ought to be relatable, ought to respond readily to the advances of readerly identification, does, indeed, pose a pedagogical challenge. I, too, want my students to think about the choices that go into crafting a character and the implicit formal laws by which a character must abide, rather than simply responding to that character as if it were fully human.

However, I think this impulse to connect (or to seek connection where it is found lacking) also holds the potential to open up fruitful conversations in the classroom about how we read now (and how they used to read back then). In particular, I aim here to sketch out a series of attempts to use contemporary texts to disrupt students’ assumptions about their emotional and psychological distance from Romantic-era fiction. Rather than dismissing talk of readerly identification, I have attempted to leverage my students’ desire to relate in order to launch a discussion of historical reading practices and the emergence of relatability as a value. To put it another way, I use my classroom as a site for uncovering the prehistory of relatability. These conversations require both careful historicizing and, at the same time, a willingness to remain limber enough to move between kinds of texts, between kinds of attention, and between points in time.

My current thoughts on these questions were prompted by an obstacle I encountered while teaching a unit on sentimental reading in my Gothic novel course. My aim in this series of class meetings was to help students connect the sentimental novel to the Gothic as they completed Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and took up Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey (1817). I provided them with background on the culture of sensibility, and we read passages from eighteenth-century letters describing the (for my students, peculiarly) physical response readers had to novels like Clarissa (such as Sarah Fielding’s Remarks on Clarissa [1749]: “Tears without Number have I shed . . .”; or her brother Henry’s letter to Richardson: “I then melt into Compassion, and find what is called an Effeminate Relief for my Terror”). This background reading informed our discussion of Austen’s famous defense of novel reading and, as I argued, its inextricability from an understanding of novel reading as a shared experience. You’re no doubt familiar with Austen’s digression: ‘if a rainy morning deprived [Catherine and Isabella] of other enjoyments, they were still resolute in meeting in defiance of wet and dirt, and shut themselves up, to read novels together. Yes, novels;—for I will not adopt the ungenerous and impolitic custom so common with novel writers, of degrading by their contemptuous censure the very performances, to the number of which they are themselves adding—joining with their greatest enemies in bestowing the harshest epithets on such works, and scarcely ever permitting them to be read by their own heroine, who, if she accidentally take up a novel, is sure to turn over its insipid pages with disgust. (23)’ I won’t rehash here the contours of a discussion I’m sure many of my readers have led in their own classrooms, but I will say that the discussion of Northanger Abbey in my classroom tends to highlight the ways that novel reading as a practice is experienced as both performed and shared—from Catherine and Isabella’s relentlessly annoying, fashionable slang (“[A]re [the novels] all horrid, are you sure they are all horrid?”) to the moment when Eleanor Tilney throws her brother under the bus in Catherine’s presence, outing him as a selfish, solitary reader: “I remember that you undertook to read [The Mysteries of Udolpho] aloud to me, and that when I was called away for only five minutes to answer a note, instead of waiting for me, you took the volume into the Hermitage-walk, and I was obliged to stay till you had finished it” (77). My students and I use these passages (and others) to think about the ways that reading practices are both representative of cultural trends and, at the same time, constitutive of character.

While this particular course had gone well up to this point, in this unit I found it difficult to help my students consider the socio-historical specificity of the culture of sensibility without dismissing out of hand the reading practices we were discussing, most of which they found simply bizarre. My students, in a rare united voice, expressed a knowing disdain for the reading practices of the readers and protagonists of Gothic fiction. The complaint concentrated around a claim about unbridgeable historical distance: people just aren’t like that these days (and so, it followed, my students couldn’t be expected to understand these aberrant historical creatures). It seems to me that the choice before me in this kind of moment is between, on the one hand, taking advantage of that historical distance and, on the other, mitigating it. In this particular instance, when what I wanted my students to understand was precisely the collective experience of immersive reading, I chose the latter.

Trying to find an analog for these intense—and shared—emotional experiences of literary texts, I came to our next class armed with examples from our contemporary culture: YouTube reaction videos.

In case you’re not familiar: these curious short films document a particular viewer’s experience of a text (in some cases, a Twilight movie trailer or another fitting example of the neo-Gothic), depicting moments of intense affective response alongside a running narrative of that response provided for the benefit of the reader. Consider the case of Nutty Madam, a devoted “Twi-hard” who posts short videos to discuss the Twilight novels and to react to film trailers, celebrity gossip, or book news. Nutty Madam shrieks, sobs, covers her mouth or her eyes, bounces urgently in anticipation of a particular character’s appearance on screen. She leans in closer to her webcam until her face floods the screen, and then flings herself away from her computer, disappearing from view entirely. She is utterly solitary (never joined by a fellow host) but also affectionately chummy with her viewers, greeting them with an eager “Hiya!” and joining the conversation in the (always lengthy, sometimes nasty) comment threads below. She has, by virtue of her videos, become a minor celebrity; she is invited to film premieres and tasked by various entertainment news outlets with interviewing actors.

Invariably, the creators of these reaction videos fill their (and our) screens, their legible facial expressions clearly the main event. In most cases, the viewer does not actually see what the subject is seeing (though in rare cases an inset image displays the clip that is being responded to). Often, however, the videos assume prior knowledge of the clip being viewed by the subject. In other words, the reaction of the subject is more entertaining if the viewer can, on her own, anticipate and then call up the particular images that are eliciting a corresponding response from the subject. In this way, the videos experiment with a kind of asynchronous shared viewing experience, even as the subject draws particular attention and the viewer sharing this experience remains unknown (save for any supplementary interaction in the comments). This shared viewing is complicated further by the fact that the clips to which subjects react are often adaptations; this means that levels of familiarity with the shared text are layered. When watching the reaction to a movie trailer, for example, a viewer may be looking for both the response to the trailer which she has already seen and, at the same time, the response to a depiction that deviates in some way from a representation in the book both she and the subject have previously read.

These videos, like the novels we discussed in class, triangulate the experience of readerly interaction in a fascinating—if somewhat unsettling—way. Our viewings led to a lively discussion about the physical performance of affect, about both Romantic and contemporary fandoms (subcultures organized around shared fascinations with a particular cultural phenomenon), and about why certain characters might be more likely to provoke an intense response of identification or revulsion (for more on Romantic fandom, see Eisner; on fandom more broadly, see Jamison). This discussion also led to a serious consideration of how gender expectations figure into our understanding of companionate reading and performed emotion. My students, most of them women, traced some of their own initial distaste to concerns about the performance of affect as the performance of a certain kind of femininity (and, in particular, to a sense that to cry publicly would mean exposing vulnerability). These concerns seemed to be troubled, if not resolved, by the realization that the work of orchestrating and then broadcasting public crying imbricates vulnerability with authority.

At my students’ prompting, we looked at other subgenres of reaction videos, including those that documented responses to sports losses or victories (a subject bursts into tears after a winning World Cup goal, the camera squarely focused on his face to capture a live, real-time reaction) and the wildly popular reaction videos showing viewers of the HBO series Game of Thrones (a bar full of subjects scream in horror and peer through their fingers when viewing a particularly grisly scene); many of these reaction videos featured men exhibiting the same intense physical responses we’d already seen (on Game of Thrones reaction videos, see Hudson). Our discussion of gender became more complex as we built our network of examples and then returned to the novel. (As if to provide additional fodder for this unit, Stephenie Meyer has since published a gender-swapped “reimagining” of Twilight, a reengagement with her own source material that we might think of as a kind of self-reflexive fan fiction.)

I want to stress that the obstacle I encountered in teaching my students about the culture of sentiment was not that students too eagerly invested themselves in these characters and their lives. Rather (and, I think, typically), they were, at first, quite sure that these texts were alien to them, to the point of presumed unknowability. To help them explore their own reactions, I didn’t just present them with evidence that these characters were in fact relatable (by showing how those characters were like characters my students expressed more comfort sympathizing with). Instead, we looked at contemporary texts that tend also to seem strange or unknowable, texts that may be familiar by virtue of their recognizable allusions or reference points, but that, for many of my students, still inspired feelings of unease or even disapproval. Indeed, I’m dubious of the idea that using contemporary texts is only useful as a kind of incentive to coax students to read texts about which they would otherwise voice reluctance (a carrot to lead them ever further into the past). While many of my (in this case, mostly young and female) students were still ready to hold the (again, mostly, though not only, young and female) YouTube hosts in contempt, this response started to break down over the course of our discussion, and started to become a curious (but productive) blend of critical engagement and empathy. I know I’m far from alone in making these kinds of connections. In a brilliant essay, “Our Bella, Ourselves,” Sarah Blackwood has written of the resistance she met with when teaching another late-eighteenth century sentimental novel, Charlotte Temple (1791): her students “complain that all Charlotte does is swoon and cry. She isn’t ‘a strong heroine’ they protest.” Blackwood likewise sees the Twilight Saga as a way to invigorate often difficult class discussions: “to revitalize a number of our larger conversations about feminism, especially those related to sex, pregnancy, desire, and autonomy.” This investigation is possible not because her students would rather talk about Twilight than Charlotte Temple, but because her students reject Twilight for the same reasons they reject Charlotte Temple. The juxtaposition helps them (and us) start to think about why.

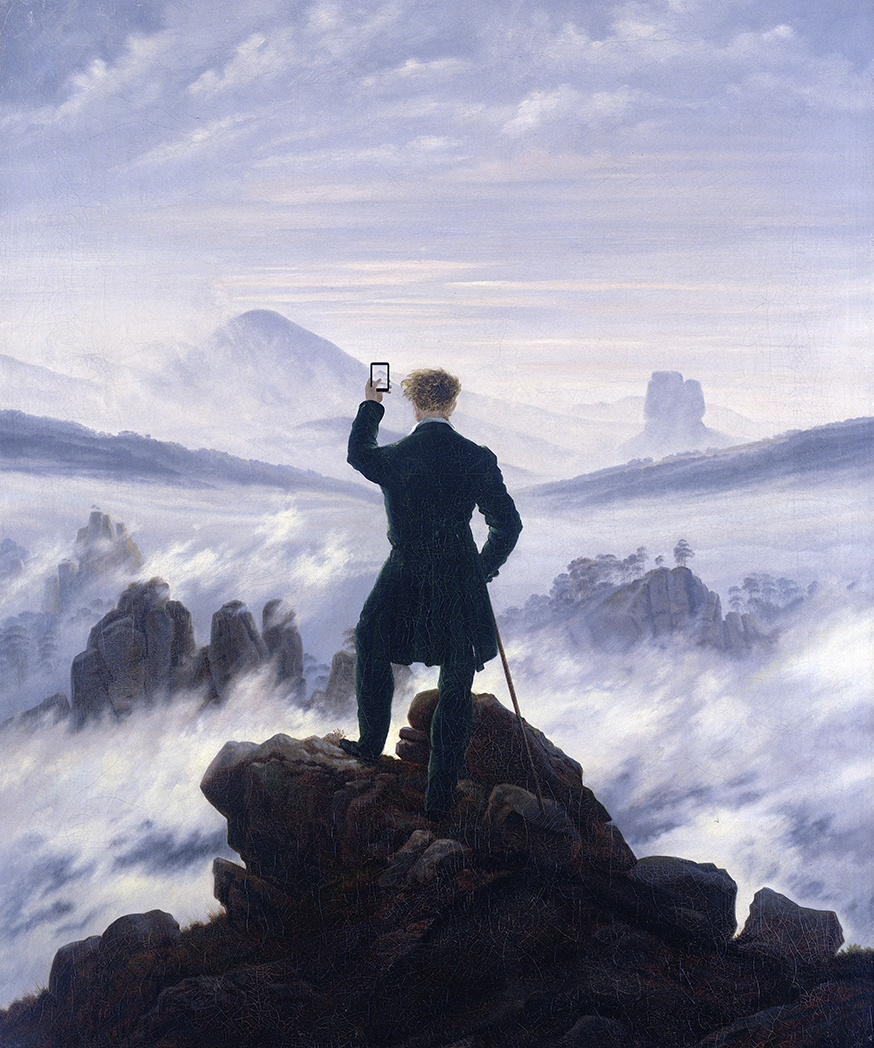

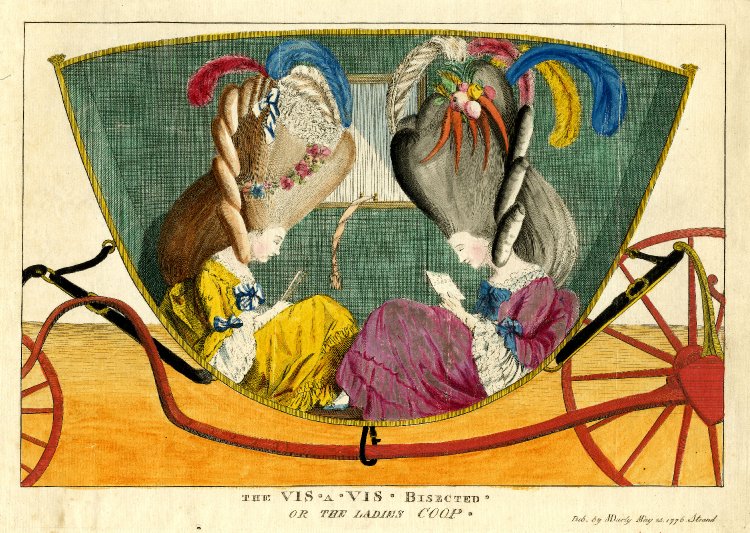

Building on our conversation about reaction videos, I also showed students this caricature of two young women reading together in a vis-à-vis carriage. In doing so, I quite pointedly wrested the image from its historical context. (The caricature is poking fun at fashionability more than it is demonstrating companionate reading.) One serendipitous visual effect is that the young ladies’ letters look (at least to me and to my students) startlingly like our modern electronic devices; like passengers on the Subway, they aren’t, as the name of their conveyance would otherwise suggest, “face-to-face” but staring down, intent on their reading. The time warp of the image is immediately suggestive; the figures in the image seem both of their time and alarmingly familiar. That hunch, that stare are a part of our own muscle memory. This familiarizing effect allows the image to raise questions about our own habits of media consumption: Can immersion coexist with shared intimacy? When we stare at screens, do we necessarily shut out those around us? And what of the intimacy we share with those we encounter on the screen (or on the page)? A similar effect is produced by the work of digital artist Kim Dong-Kyu, whose “When You See an Amazing Sight”—featured at the beginning of this essay—wrenches perhaps the most clichéd image of the Romantic sublime into a commentary on our modern tendency to document rather than experience. The commentary, like the discussions I try to have in my classes, raises questions about just how different our contemporary phenomenology might be: was the Romantic sublime ever purely experienced? Or are paintings like Friedrich’s (and, we might add, poems like Shelley’s or essays like Burke’s) analogous at all to our Facebook posts? Was the Claude glass an Instagram filter? What difference does the immediacy of (iPhone) photography make to the registration of aesthetic experience? Can we constantly document our lives and still “recollect in tranquility”? (I’m reminded of my beloved high school English teacher’s story of her visit to Tintern Abbey: She gasped upon seeing the abbey on her first trip outside of the US, dropping her camera and breaking it beyond repair. In tears, she comforted herself by repeating, “It’s what Wordsworth would have wanted. It’s what Wordsworth would have wanted.”) As I hope these questions suggest, it’s crucial for me to bring these texts into conversation with each other in order to provoke a discussion of both the Romantic texts and the contemporary phenomena. It’s all too easy to fall into what Ted Underwood has called, in his valuable discussion of using pop lyrics in the classroom, “the naïve assumption that popular culture is absorbed directly by the ears, and that only high culture has to be mediated through the analytic intelligence” (12). These discussions only work, in my experience, if my students and I are invested together in examining our own practices along with those of the historical figures we’re studying.

While I would contend that these kinds of metacritical discussions could be valuable in a variety of classes, courses in Romantic fiction are uniquely situated to explore the complexity of students’ responses to fictional character. This is because, as Deidre Shauna Lynch has shown, “It is romantic-period characters who first succeed in prompting their readers to conceive of them as beings who take on lives of their own and who thereby escape their social as well as their textual contexts” (8). Lynch makes clear that Romantic fiction mobilized a complex response to literary character that can’t simply be summed up with the term “identification” or “relatability”:‘Identification, the modern term for what we do with characters . . . . obscures the historical specificity, the relative novelty, of our codes of reading. With the beginnings of the late eighteenth century’s ‘affective revolution’ and the advent of new linkages between novel reading, moral training, and self-culture, character reading was reinvented as an occasion when readers found themselves and plumbed their own interior resources of sensibility by plumbing characters’ hidden depths. (10)’ Lynch is certainly right to encourage us to develop more specificity when exploring the historical dimensions of character in our scholarship. At the same time, it’s clear that “identification” and “relatability” are, however diluted, part of the legacy of this Romantic revolution in the long history of reading. For that reason alone, it’s worth reconsidering their role in our classrooms.

We take a risk when we assume that students are just trying to relate to everything and are eliding differences along the way. So much of what I expose my students to is unknown to them. Why rob them of what isn’t? Relatability, as I see it, isn’t a way for them to dig out; it’s a way for them to get in. We can all relate (sorry!) to Michael Warner’s characterization of his classroom: “Students who come to my literature classes, I find, read in all the ways they aren’t supposed to. They identify with characters” (13). But Warner’s argument is that we can only figure out what we mean by “critical reading” if we allow ourselves to consider it as always bound up in relation to its uncritical other. I share with critics of relatability a frustration with inert critical responses—the sort that shut down or close off analysis rather than encouraging it. But I’m less convinced that “relatable” is more disposed to this kind of danger than any other initial response to literary fiction. In fact, in my experience, relatable (and, crucially, the kinds of probing questions that it necessarily prompts) holds particular potential to compel students to trace their responses back to their textual causes, to think through the intricacy of their connections to Romantic texts. To scrub the term from our classrooms is to foreclose serious discussions of the complex work that goes into (and has long gone into) novel reading.